Walking The Ridgeway, by Anthony Burton

Anthony Burton is author of the official guide and presenter of the new DVD on The Ridgeway, avalable from TVWalks.com. See foot of the page for more details

The Ridgeway offers a journey through magnificent scenery, and also a passage through time. This is an ancient track, so old that no one can even put a date on it – all we can say is that it was almost certainly in use as a trading route in the New Stone Age, and that began about 6000 years ago. Monuments from the past can be found all along the way – this is a walk that has Britain’s biggest henge monument at one end – and, yes, it really is bigger than Stonehenge – and an Iron Age hill fort at the other, and most other ages represented in between. This sense of the past would be enough to attract many people to this famous long distance footpath, but it is by no means the only reason. For a start, the route lies within two areas officially designated as Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty: the North Wessex Downs and the Chiltern Hills.

Although, as the name suggests, the route runs mainly along the top of a chalk ridge, that does not mean there is no variety in the scenery. Starting in the west, the route across Marlborough Downs is exhilarating: a walk in open country of swelling hills and wide vistas. You will find yourself walking along an escarpment edge, with immense views to the north across the Vale of the White Horse, while to the south there is a complex pattern of dips and folds. It all remains very open until the path begins to dip down to cross the Thames at Goring. Once the Thames valley has been left behind, and the Ridgeway has resumed its eastward line, the scenery begins to change, but now woodland is a dominant feature in the scenery. Nearing the eastern end the walk calls in at small villages and towns, before ending in the spectacular upland of Ivinghoe Beacon. It makes a fitting end to this spectacular National Trail.

The two most often asked questions about the walk are: which way should I walk and when should I go? Most agree that walking west to east is preferable, mainly because our prevailing winds are westerlies. That means you get a help along the way on a fine day and you don’t get rain in your face when it’s wet. The other question is more difficult. My personal preferences are for spring and autumn; there is not much shade for much of the route so summer sun can be a problem and winter has the obvious disadvantage of short days. There is a positive side as well to the other options, particularly at the eastern end, when the woods are a mass of bluebells in spring, while the beech trees are at their finest in autumn. In the end, it is all a matter of individual preference – you can look forward to a splendid walk no matter when you go.

To whet the appetite, here’s a foretaste of 87 miles of splendid walking.

Overton Hill to Ogbourne St. George (9½ miles, 15km)

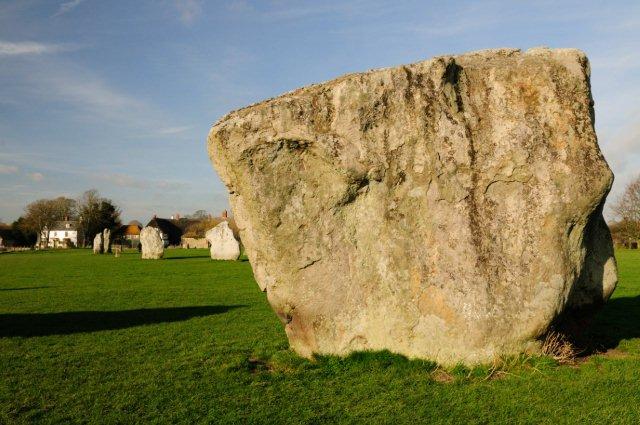

This is rather a short section, but it allows time for a diversion to Avebury. The walk starts at a lay-by on the busy A4, west of Marlborough, a nondescript spot to the modern motorist, but significant in terms of prehistory. On the southern side of the road are the scant remains of a stone circle, known as The Sanctuary and around it are prominent mounds, that are Bronze Age round barrows, ancient burial mounds. The obvious track leads north, and almost at once the views begin to open out over the downland. There is a steady climb, and in the grassland to the right, grey shapes can be seen, that might just about be mistaken for sheep, hence their name, “grey wethers” – an old name for sheep. These are the sarsen stones, similar to those which were dragged down the hillside to create the stone circles of Avebury. Near the top of the hill, there is a crossing of tracks as the Ridgeway meets another old route, a herepath (an unsurfaced, Saxon military road – ED), dating from Saxon times. It leads down to Avebury, and for anyone who has not visited that amazing site, it is well worth a diversion. Meanwhile the main route continues up to the top of the ridge, with the views getting better and better, until a grand panorama is visible over to the west, and the walker may well find a musical accompaniment, as a skylark sings above the downs.

The top of the climb is marked by a trig point, just beyond which is a road with a car park above a white horse cut into the hillside – not the famous white horse that gave its name to the Vale, which we’ll meet later. The track continues its high level route, and as it swings east, the view starts to include the tower blocks of distant Swindon, but there is another exciting prehistoric site just ahead, Barbury Castle. This is no fortress of stone, but an Iron Age hill fort, protected by massive earth ramparts and deep ditches. The walk goes straight through the middle to emerge onto a pleasant grassy track that leads to a car park and picnic area. Beyond that the ridge continues, and now this is downland walking at its very best: springy turf underfoot, a high ridge that forms a sinuous line above the valleys of Ogbourne Down and marvellous views. It is almost a disappointment when it ends, and the track begins to head downhill towards the village and the valley of the little River Og.

Ogbourne St. George to Sparsholt Firs (16 miles, 26 km)

The path doesn’t actually go into the village – though it’s only a short way off route – but instead follows the wandering river round to the lovely little hamlet of Southend. The route continues, crossing the busy main road, under the remains of a bridge that once carried the railway from Swindon to Marlborough and across the typical straight line of a former Roman road. This is a steady climb, up a deep, sunken lane, overhung by trees that eventually leads back at the ridge, but now surrounded by arable farmland. This section of the ridge ends at another hill fort, Liddington Castle. There is a steep descent, down to a road that crosses over the M4 to arrive at Fox Hill and the Shepherds Rest pub – as this is the only pub right next to the route in the first half of the walk, it often turns out to be a walkers’ rest as well.

The route leaves the road to climb up Fox Hill, back to the top of the ridge. For a lot of the way, the track runs between hedgerows near the escarpment edge, but where there are breaks, more fine views appear, down to the villages in the Vale. The Ridgeway now enters one of its most dramatic and historic sections. The first site is just off the main route, Wayland’s Smithy. This is a Neolithic long barrow, begun nearly 5000 years ago, a huge mound covering stone burial chambers, with immense sarsen stones set all round it. Just up ahead is Uffington Castle, one of the grandest of all the Iron Age forts and near that on the hillside is another White Horse. This time, it really is the horse that gave the Vale of the White Horse its name. For a long time there was doubt about its age, but recent scientific research has shown that it was first carved right back in the Bronze Age, a remarkable monument. Such a wealth of prehistoric remains would be quite enough on their own to make this part of the walk special, but the superb scenery makes it simply magnificent.

This is also an area where white horses created out of chalk are not the only equine inhabitants: the downs are used as gallops for the racing stables that cluster at the foot of Lambourne Down. There is one more climb to the top of Sparsholt Down, the highest point on this section of the Ridgeway. It was an area loved by a boy called Peter Wren and when he died at the age of 14 an engraved stone was placed here and a very practical tribute, a water tap for thirsty walkers and a trough for horses. From here, there are more gentle undulations, but this section ends at the road by the coppice of Sparsholt Firs.

Sparsholt Firs to Streatley (17½ miles, 28 km)

Crossing over the road brings the walker out above another spectacular feature: the land to the north drops away sharply to a shapely hollow, known as the Devil’s Punch Bowl. There is pleasant walking on a broad, grassy track that leads on to yet another hill fort, and it is also a place that provides evidence that the Ridgeway was there before the fort. Most hill forts have regular, curved ramparts, but this one has a straight line all down one side so as not to get in the way of the ancient track. This is an area full of interest and contrasts. Patches of woodland now dot the land, and the ploughed fields when seen in winter seem to have a dusting of snow, but that turns out to be just the white speckles of the chalk, which is never far from the surface. The track arrives at a B-road that leads down to the ancient town of Wantage, said to be the birthplace of Alfred the Great, but the path continues straight on, heading towards a prominent landmark, the monument to Baron Wantage (1831-1902). It records the Crimean War battles in which he served, but there is a very different monument to him here as well. He developed the Lockinge Estate that surrounds the Ridgeway, with its appealing patchwork of copses. Once past the monument the vistas open out again, with views that on a good day stretch all the way to Oxford. There is one feature, however, which you can’t miss – the cooling towers of Didcot power station, often sending their plumes of steam stretching across the surrounding countryside.

The broad track continues to a clump of trees with a mound in the middle, known as Scutchamer Knob. No one seems quite sure where the odd name originates, though the most popular suggests that it was the burial mound of a Saxon king Cwicchelm. It looks remarkably like a typical round barrow, but walkers can feel free to invent their own theories. The next part of the route is quite flat and heads off to the very busy A 34(T). Fortunately, there is no need to brave the traffic as there is a short tunnel through the road embankment. Emerging on the far side the route passes above Sheep Down. Once the area was famous for its flocks, but now it has been mostly ploughed over, and the busy sheep markets of East and West Ilsley are just a memory. The downs, however, have lost none of their charm and they are still home to galloping racehorses. The track crosses a disused railway, the grandly named Didcot, Newbury and Southampton Junction. Sadly, its performance was less grand than its title: begun in 1882 it was closed before it reached its centenary.

There is now a notable change in the landscape, with woodland becoming ever more prominent. The thin soil of the chalk downs is giving way to richer land that can support more farms and the grass is now munched by cattle as well as sheep. It is an area notable for wide views, but can have its surprises. A deep valley suddenly falls away to the south, smooth sided with a headland planted with a small copse. This is Streatley Warren, a name that tells us that this was once a home for rabbits – and still is, a fact not lost on the local bird population. Look up, and chances are you will see a buzzard or kestrel circling overhead. The route heads down hill along the very attractive valley to arrive at the main road that leads down to Streatley.

Streatley to Watlington Hill Road (15 miles, 24 km)

Streatley is a little town full of character, where elegantly sophisticated Georgian houses happily sit beside homely thatched cottages. The town developed here, because this is the point where the Thames makes its break through the Chiltern hills, creating an obvious crossing point. Everything is squeezed into the gap – river, road and railway, but it is the river that demands attention. A complex of weirs send the water churning into a foam, leaving a narrow channel at the far bank to hold the passage for boats and the lock to raise and lower them to the different levels. Astonishingly, before the lock was built in the 18th century, the weirs had movable paddles that held back the water, and when they were removed, boats used to ride down on the “flash” of water – hence the name flash lock – or be winched up against the flow. It sounds dangerous and it was – in 1634 a passenger boat overturned with the loss of over sixty lives. The bridge leads across to Streatley’s neighbour, Goring with its old water mill.

The route now follows the line of the Thames, passing through the village of South Stoke, with a modest church that contains one imposing memorial to Dr. Griffith Higgs, born in 1589 and at one time Chaplain to the Queen of Bohemia – not quite what you expect in a modest English country church. The next village, unsurprisingly called North Stoke, also has a church with a surprise inside, a set of medieval wall paintings. The path stays close to the river as far as the outskirts of Wallingford, which is well worth a short detour. It dates back to Saxon times, when it was one of a series of “burhs” or fortified towns, and parts of the old town walls still remain.

Meanwhile the Ridgeway turns away from the river to continue heading off to the east and the Chiltern Hills. It follows a curious man-made feature, known as Grim’s Ditch, and its true nature becomes clearer as you walk along, when the ditch becomes ever deeper and its accompanying bank even higher. No one knows when it was built or why – the best bets are Iron Age and that it was some sort of boundary marker. Along the way, it crosses another ancient track, the Icknield Way, which turns up again along the way, before heading off to an area of mixed woodland. The final stretch of Grim’s Ditch is the most dramatic, running through a parade of mature beech trees. It continues to the top of the hill, where the ditch ends and the Ridgeway turns away towards the village of Nuffield. Here is yet another church with a history to tell: it stands on the site of a Roman villa, and many of the original Roman bricks and tiles were built into its fabric.

From Nuffield the route crosses the main road and heads off towards Ewelme Park. The house is not quite as old as it seems: it is one of those very charming vernacular buildings that were built in Edwardian Britain, and this is by one of the main architects of the movement, Charles Voysey. Strutting peacocks and their dowdier female companions generally give walkers a raucous welcome. The walk continues past another grand mansion, Swyncombe Park, which remains tantalisingly out of sight behind high walls, but for those who come this way in spring there is more than adequate compensation: the area is famous for its snowdrops. The tiny hamlet of Swyncombe boasts a small but ornate church almost dwarfed by its rectory.

Watlington Hill Road to Wendover (17 miles, 27km)

The next part of the route runs along the foot of the hills for a change, a more or less straight track through farmland, and eventually arrives at the M40. The motorway drives through the hills in a deep, chalky cutting, but the Ridgeway trail leads walkers safely through an underpass. It emerges beside Beacon Hill and the Aston Rowant Nature Reserve, home to the rare Chiltern gentian and the very local Chalkhill Blue butterfly. The path crosses over the A 40, now quite peaceful after the arrival of the motorway. As the noise of traffic recedes, the walk becomes much more pleasant, along a bridleway enclosed by trees. Should you happen to hear thundering hooves, then you have probably arrived on one of the rare race days at Kingston racecourse. Up ahead, the view is dominated by the tall chimney of Chinnor cement works, and you soon find out why it was built just here. The path runs past a series of old chalk pits, now mainly flooded and looking quite exotic, the chalk turning the water to a turquoise blue, the sort of colour that makes you think of tropical islands not English hills. And hills and woodland now begin to dominate the walk. It makes for a rich and varied section, sometimes enclosed by trees, then opening out to fine views out over the Oxfordshire plain.

The route heads down past a golf course for the railway, which for once is still running. It is part of the last main line to be built in Britain, the Great Central Railway, and here it dives down through a deep cutting to the short Saunderton tunnel. The route skirts the edge of Princes Risborough, before heading for another attractive area of wooded hills, to take a path that meanders through the trees to emerge at the Boer War monument on Combe Hill. This is a splendid viewpoint and a panorama points out the places of interest that you can see – though for some of them you might need the help of rather good binoculars and a very clear day. Having enjoyed the view, it is time to head downhill once again and follow the track into Wendover.

Wendover to Ivinghoe Beacon (12 miles, 19km)

Wendover is the only town of any size that the walk actually goes through, but when it’s a town as attractive as this it is a pleasure rather than a nuisance. This is an old market town that shows its age in a fine mixture of buildings, many of them timber framed. The route out of town heads back uphill for another woodland walk, which turns out to be something of a switchback, reaching the top, taking a hollow way down and then climbing back up again. But with mature, broad leaf woodland like this no one minds putting in a bit of extra effort. There is a short break out in the open, then a walk through a very different type of wood. This is Tring Park, part of the former Rothschild estate, laid out as a formal drive along an avenue of lime trees. Then the route swoops back down again for the final visit to the valley floor.

The path joins the road for a while to cross two other transport routes, the canal and the railway. When William Jessop came to build the canal, now known as the Grand Union, in the 18th century he found this to be the best place to pierce the hills, so he set his canal in a deep cutting. In the next century, Robert Stephenson came here to build his railway from London to Birmingham and came to the same conclusion, even if the result was that Tring station is nowhere near the town.

Now the walk heads back uphill again to woodland and arrives at another Grim’s Ditch – which is probably associated with the one met earlier. Where there is a break in the trees, the view opens down to the old Pitstone windmill – and the end of the walk comes into sight.

The final part of the Ridgeway is a fitting climax, an exhilarating walk over open grassland. The track swings round above the steep sided cleft of Incombe Hole before climbing to the headland that marks the end of the ridge and the end of this walk. There is time to look out over the wide plain opening out in front and back over the long line of hills and, of course, time to congratulate yourself on finishing one of Britain’s finest long distance trails.

READ THE BOOK – SEE THE FILM

The official guide to the National Trail is published by Aurum Press in association with Natural England. It has detailed descriptions of the entire route accompanied by maps specially prepared by the Ordnance Survey, based on the 1:25,000 Explorer maps. It is fully illustrated with specially commissioned photographs, and as well as the detailed notes on the route, there is an introduction to the Trail and lots of information about places of interest met along the way. There are also five circular walks for those who would like to explore more of the countryside around the Ridgeway.

Anthony Burton, The Ridgeway, Aurum Press

For those who want to get a real feel for the whole walk before setting out or a reminder of its pleasures after finishing, Anthony Burton is your guide on a filmed tour of the Ridgeway, featuring all his favourite scenic sections and a selection of some of the fascinating places you can visit. It is available as a DVD or as a direct download from the website. Full details and a short trailer can be found at www.tvwalks.com.

Buy the DVD online, at a special 25% discount for Members of the Friends of The Ridgeway: only £9.00 plus p&p. Click here to go to tvwalks.com, and use the code published in the latest copy of the Newsletter. You will need to key the code into the ‘Voucher Code’ box which appears on the page where you choose your payment preference.

All photographs in this section of the website come from the Ridgeway DVD and are © Bonza TV Ltd.