The Ancient Ridgeway

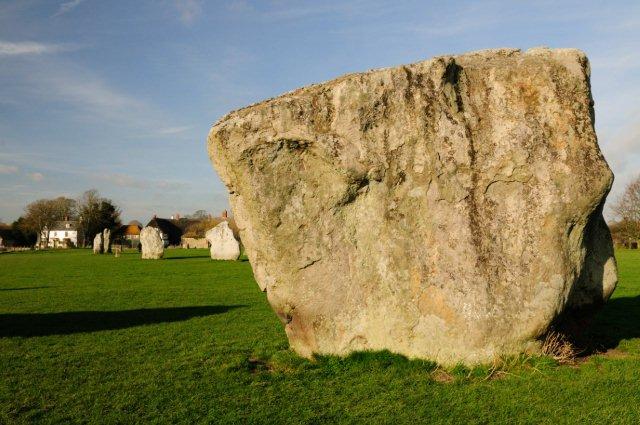

The great megalithic enclosures or henges of Stonehenge and Avebury in Wiltshire bear witness to the existence over many hundreds of years of a great civilisation in this part of Wessex. This has been dated from around 5,000 to 3,500 years ago, straddling the Neolithic and Bronze ages. The sheer amount of labour required to excavate the huge ditches, to gather, transport and erect the massive stones, and to raise the strange mound of Silbury Hill, indicates the availability of a substantial population, and the quality of the work, particularly in the latter stages, shows their considerable skills. Grave goods and artefacts found on site provide evidence that there were movements of people and objects between this culture and others in Europe, and it is probable that there was extensive trade not only within England but across the Channel and the Irish Sea, with bronze and tin, amber and gold, and possibly many other goods, being exchanged in increasing quantities. It has been proposed that this part of Wessex marked the boundary between an Atlantic and a Continental culture.

The movement of goods in trade pre-supposes routes for the passage of people and animals. In pre-historic times the chalk up-lands, free-draining and relatively open, with scrubland, grazing animals and primitive cultivation, offered easier and safer passage than the heavy clay and dense woodland of the vales and river valleys, particularly in winter. The geological map shows a band of underlying chalk running diagonally across Southern England from East Anglia and the Wash to the Devon and Dorset Coast. The central and southern parts of this band form the great escarpment of the Chiltern Hills and the Wessex Downs. Upland trade routes from the centre of the Wessex civilisation lead north to the Cotswolds, east along the North Downs to Surrey and Kent (The Harroway), and south-eastwards to Winchester and the South Downs; but the main artery led south and west to the harbours of Devon and Dorset, and north-east towards East Anglia, for 400 miles from coast to coast along the edge of the chalk, and this great highway is the ancient Ridgeway.

The Ridgeway, like other pre-historic routes, was never a single, designated road, but rather a complex of braided tracks, with subsidiary ways diverging and coming together. Successive ages made use of the route for their own purposes, and left the marks of their passage. Pre-historic barrows and burial mounds, like Wayland’s Smithy, line the route and excavations have found implements and ornaments from many sources.

As the land lower down the slopes was cleared, a lower route became feasible in summer, closer to the spring line where water was accessible to travellers and their mounts. While The Ridgeway followed the top of the downs the Lower, or Icknield Way, runs parallel to it just above the foot of the slope, as far south as Wanborough near Swindon. To the north of the Chilterns, where the chalk is flatter, the routes come together. The Icknield Way was used and upgraded by the Romans for much of its length for both trade and military purposes.

The Ridgeway links many of our finest Iron Age hill-forts and monuments including Uffington Castle and the White Horse. It is today believed that the hill forts were not primarily used for defensive purposes, but were rather community centres, in which Iron Age tribes or clans gathered for worship, feasting and to trade livestock, crops and other goods. However, they provided a convenient defensive line of redoubts linked by The Ridgeway when the Romanised Britons were under threat from Saxon invaders, and later again for the Saxons themselves against their Danish and Norsemen foes. In the modern era, traffic on The Ridgeway declined, and its main use was as a droving route, until its rediscovery as a precious resource for access to the countryside and our ancient heritage.

This network of ancient tracks or greenways was amongst the first of the long-distance paths recommended for creation by the Hobhouse Committee in 1947 as one of the first “long distance paths”, later known as National Trails. However, in the event only a much-shortened central section, between Overton Hill near Avebury in Wiltshire, and Ivinghoe Beacon in Buckinghamshire, was approved in 1972 as The Ridgeway National Trail. Most of the remainder has been way-marked, however, and is shown on OS maps, under different names. The Icknield Way route running north from Ivinghoe Beacon follows the ancient road by green lanes along the lowland chalk through the Breckland and past Newmarket to end at Knettishall Heath south of Thetford (110 miles). A Roman road, the Peddars Way, now a National Trail, runs northwards from Knettishall to Hunstanton on the Wash (49 miles), and thence as the Norfolk Coast Path, to Holme-next-the-Sea and the Seahenge monument, contemporary with Stonehenge.

To the south, the Wessex Ridgeway path runs from Marlborough and Avebury along the northern and western edge of Salisbury Plain and the Dorset Downs, via Devizes, Warminster, Heytesbury, Hindon and Tollard Royal, to the South Coast at Lyme Regis (136 miles). Like The Ridgeway, this path links a number of iron-age hill forts, and provides excellent walking along high chalk downs, with extensive views. The section of the Wessex Ridgeway in Dorset (63 miles) has been up-graded to National Trail standards by the Dorset Countryside Ranger Service under a LEADER project. A long-distance route, referred to by the Ramblers Association as the Greater Ridgeway, following most of these paths, totals 363 miles and is detailed in a published guide-book by Ray Quinlan.

There remains, however, a missing section, which starts with the southwards extension of the ancient Ridgeway, shown as such on the OS maps, from the present end of The Ridgeway National Trail at Overton Hill and Avebury across the Downs to the Wansdyke, Knap Hill and Alton Priors, in the Vale of Pewsey, where the ancient route was obliterated by the Kennet canal. The Friends of The Ridgeway believes, however, that this route, part of the ancient Ridgeway, connecting the great centres of Avebury and Stonehenge, should be revived and proposes to identify it as The Great Stones Way. We postulate that it ran southwards across the Vale and up onto Salisbury Plain at Broadbury Banks, and thence via Casterley Camp above the Avon Valley by the most direct route possible, avoiding the military ranges across Salisbury Plain, to Durrington Walls, Woodhenge and the prime national monument of Stonehenge. From Stonehenge the route continues southwards to Old Sarum and Salisbury. We hope later to see the path extended across Cranborne Chase to Whitesheet Hill and Win Green, where it will rejoin the Wessex Ridgeway.

The Great Stones Way and its extension will complete the ancient Ridgeway route across Wessex, and its epicentre at Avebury and Stonehenge, from the north Norfolk coast to the Channel coast in Dorset. To walk this route in either direction, retracing the steps of pre-historic traders and pilgrims, to its climax at Stonehenge, is to get as close as we can today to the mysteries of this ancient civilisation.